In 1997, Ettore Scola, the great director who passed away in January 2016, created “La Cena” inspired by the dinners, indeed, consumed on Wednesdays by Otello at Concordia, the famous osteria we have already written about, linking it to Cesaretto and the Fratelli Menghi’s place. In Scola’s film, Vittorio Gassman, Fanny Ardant, Giancarlo Giannini, Riccardo Garrone played the roles of ordinary people: a communist intellectual, the restaurant owner, a professor, the head waiter. In the reality of Wednesdays at Otello’s, Gassman, Garrone, Giannini, Ardant (rarely, living in Paris) were themselves, in a continuous, vital alternation of truth and fiction.

Italian Cinema at the Table

Having had the privilege of regularly attending, along with many other friends, the director of “We All Loved Each Other So Much,” “A Special Day,” “The Family,” I remember that Scola liked to invite younger, less-known colleagues to dinner at Otello’s to listen to them vaguely attentively, and then stun them with a surprising humorous remark or a punctual caricature, drawn instantly with his pen, always casually.

Over the years, I have often had dinner with Scola, never lunch. Perhaps because, once the eventual lunch was over, it would still be daylight, and perhaps we would have found ourselves waiting for dinner to end the day. Perhaps. I don’t know.

A conflict difficult to resolve, that between lunch and dinner. Perhaps that’s why, still a “perhaps,” I greeted with slight disappointment the release of the book “A pranzo con Orson,” which collects conversations between Henry Jaglom and Orson Welles, the author of masterpieces like “Citizen Kane,” “The Magnificent Ambersons,” “Touch of Evil.” Jaglom and the “great wizard” Welles’ lunches, actually, seemed like dinners to me. But, beyond this certainly superfluous observation, it is a book of considerable interest that anyone who loves cinema, even generically, should read.

Between 1983 and 1985, Jaglom met Welles several times at Ma Maison, a renowned restaurant in West Hollywood, where the author of Citizen Kane often ate. “The restaurant had become his office,” recalls Patrick Terrail, the owner of Ma Maison. During lunches with Jaglom, which were weekly, the “illusionist,” as Welles liked to define himself, expressed his ideas about cinema, told anecdotes, sometimes already known but enriched with unpublished details, not hesitating to give drastic, ruthless judgments on great directors and equally great actors and actresses. To stay in culinary terms, he had no qualms about calling Marlon Brando “a little sausage.”

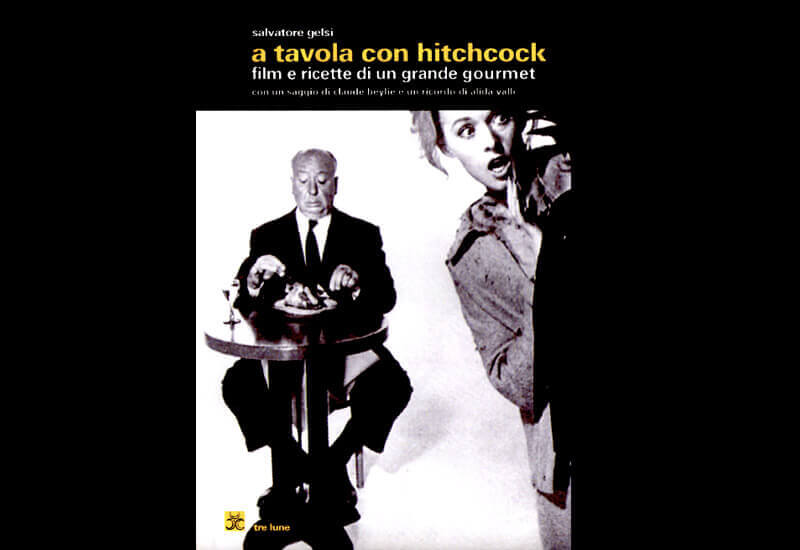

From the there with a small leap, we can find ourselves at “A tavola con Hitchcock,” the book that Salvatore Gelsi, professor of cinema and communication at the University of Ferrara, dedicated to the author of masterpieces such as “Dial M for Murder,” “Rear Window,” “Psycho,” “The Birds.” We don’t know if the great “Hitch” favored lunch over dinner, or vice versa, but his extraordinary passion for food is certain, a real creative addiction, to the point that some of his detractors claimed he made his less successful films during periods when he was on a diet.

Gelsi’s book contains, in addition to a complete biography, numerous anecdotes, and interesting considerations on how the “master of suspense” interpreted the interaction between food and sex, between food and murder. And it is surprising to read the following statement by Hitchcock: “I hate suspense; that’s why I would never allow anyone to make a soufflé at my house. My oven doesn’t have a transparent door. You should wait for forty minutes before knowing if the soufflé has succeeded, and that’s more than I can bear.”

Another leap, and we are “A tavola con Fellini,” the book that Maddalena Fellini, sister of the great director, who passed away in 2004, dedicated to Romagna cuisine and the gastronomic habits of her famous brother. It is well known that the author of “La Dolce Vita” and “8½” had Cesarina, the historic restaurant on Via Piemonte in Rome, as a reference point, where he could eat “Romagnolo” food. Less known is that he was, as testified by his closest friends and collaborators, a distracted and indecisive customer, as if he preferred the fortune teller to choose the dishes for him.

In 2013, Ettore Scola dedicated his last film, “Che strano chiamarsi Federico,” to the great director Federico Fellini. An intense, affectionate film in which the director of “We All Loved Each Other So Much,” based on his memories, recounts Fellini’s apprenticeship years at “Marc’Aurelio,” the satirical newspaper where the very young Scola also took his first steps. A true workshop of talents, the editorial staff of “Marc’Aurelio,” where many screenwriters and directors of the great Italian cinema of the post-war period were formed.

The word cinema contains the word dinner in Italian

To conclude, I would like to remember two artists who are no longer with us, two dear friends: Carlo Monni, actor/author, and formidable improviser of “octaves”; and Donato Sannini, poet and playwright, as well as the “mentor” on the transfer journey from Florence to Rome of Monni and Roberto Benigni in the distant 1972.

In the summer of 1977, Donato Sannini invited me and Monni to his large house, perhaps a castle, in San Marcello Pistoiese. The common intent was to write a screenplay for a film. During the day, the scorching heat did not favor concentration and writing. It was better to wait until the sun set and it got dark. But the night inevitably called for dinner.

At nine, we had dinner at a tavern, at the stroke of midnight at a second tavern, and around three at the tables of the local Festa dell’Unità. In those ten days, we had a lot of dinners and wrote little or nothing. Donato Sannini justified our lack of results by saying that it was inevitable that it would end that way, given that, at least in Italian, the word “cinema” contains the word “cena” (dinner).