Italian tavernas, especially those in Rome, have always enjoyed extensive and sometimes authoritative coverage. One notable example is Hans Barth’s volume, “Osteria,” published in 1909 with a preface by Gabriele D’Annunzio. In this refined text, D’Annunzio amusingly dwelled on the “Bettolino degli Svizzeri” near the Vatican, vividly depicted with a Flemish touch.

D’Annunzio wrote: “With what a fat Flemish brush you paint the Swiss tavern under the Borgia Tower! I know it well. When my life was not yet that mirror of probity and continence where the world now admires, I used to lead some young friend into the Borgian den to accomplish some sweet poisoning.”

In addition to Barth’s book, it’s worth recalling the famous photograph that Count Primoli dedicated to the Osteria del Tempo Perso in 1895, on Via Ardeatina in Rome. An extraordinary portrait of the popular and peripheral Rome of those years. Roman taverns often had picturesque but mostly descriptive names: Pastarellaro, La Matriciana, La Carbonara, Osteria della Campana, Al Moro, Scarpone, Sora Assunta, Sora Lella. Osteria del Tempo Perso, instead, is a poetic name revealing the nature of the regular tavern-goer: indolent, averse to work, with a marked tendency to dissipate time, as noted by Stendhal in his “Roman Walks” of 1829: “…work is so unnatural for a true Roman…”

From the notes of the author of “The Charterhouse of Parma,” one’s thoughts turn to the legendary aversion to work of Accattone, the protagonist of the eponymous and famous film directed by Pier Paolo Pasolini in 1960. The film, a formidable cinematic portrait of Roman suburbs, recounted the lazy days the protagonist, a “pimp” by profession, spent between a stop at the tavern or bar and improvised attempts to “turn the day around” in the company of his friends, all marked by the same destiny.

Returning to the Italian tavernas immortalized by Count Primoli, it is precisely in those years, between the late 1800s and the early 1900s, that Roman tavernas began to change their nature. From traditional places of refreshment and entertainment for common customers, they transformed into true meeting points for artists, poets, and writers. Think of Sor Antonio, in Via Vittoria, frequented by the great futurist painter Umberto Boccioni; or Pastarellaro, in Piazza San Crisogono, Trastevere, where the poet Trilussa loved to linger. In a short time, tavernas in Rome replaced literary cafes. But the real explosion of cultural tavernas occurred immediately after the end of World War II. In particular, we must remember the taverna of the Menghi brothers on Via Flaminia, Beltramme’s fiaschetteria, and Otello alla Concordia, both on Via della Croce.

The Menghi brothers’ tavern was regularly attended by important painters: Mario Mafai, Giovanni Omiccioli, Giulio Turcato, Leoncillo, Antonio Corpora, Marino Mazzacurati, Pietro Cascella, Pietro Consagra, Carla Accardi. Artists who have left their mark on the history of Italian art in the second half of the 20th century. It was also frequented by Roberto Rossellini, Anna Magnani, and Federico Fellini. Thanks to the Menghi brothers’ willingness to welcome even the poorest artists and give them credit, director Gigi Magni did not hesitate to call them “patrons.” At the tavern on Via Flaminia, the writer and screenwriter Ugo Pirro – author of the screenplays for some important films by Elio Petri, such as “Indagine su un cittadino al di sopra di ogni sospetto e La classe operaia va in paradiso” – dedicated a book in 1994, “Osteria dei Pittori,” an absolute must-read.

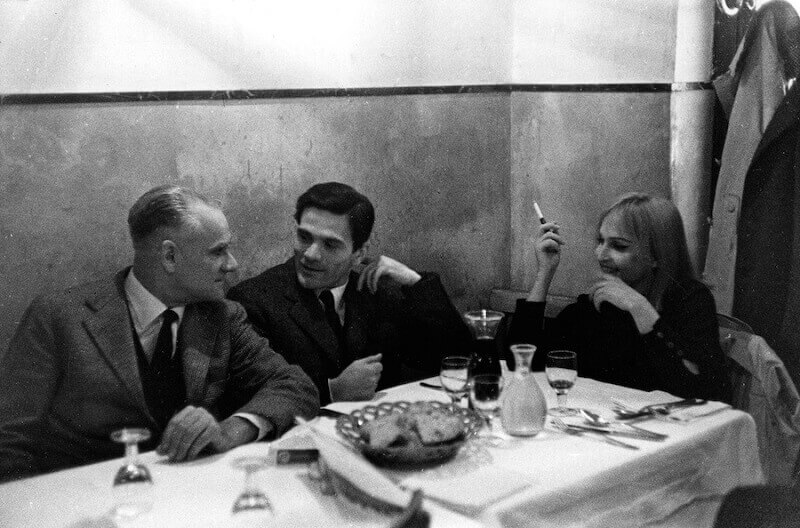

The fiaschetteria Beltramme was mainly frequented by writers: Alberto Moravia, Pier Paolo Pasolini, Mario Soldati, Ennio Flaiano, Italo Calvino. But also, from time to time, great artists like Giorgio De Chirico, Renato Guttuso, Alberto Burri. It is said that in Cesaretto Beltramme’s establishment, Federico Fellini and Ennio Flaiano conceived La Dolce Vita and Otto e mezzo. On a piece of paper from the fiaschetteria, Flaiano wrote: “Between a chicken thigh and chicory, from Cesaretto, I await glory.”

Otello alla Concordia – to which director Francesco Ranieri Martinotti dedicated a documentary film in 2012, “Otello’s Secret” – was the meeting point, almost exclusively, for directors, screenwriters, and actors of the Italian Comedy: Mario Monicelli, Ettore Scola, Luigi Magni, Furio Scarpelli, Age, Leo Benvenuti, Piero De Bernardi, Vittorio Gassman, Marcello Mastroianni.

Although I frequented all three, it is the evenings spent at Otello in the early ’90s that I remember most vividly: the communal tables – you sat where you found a place, Furio Scarpelli’s formidable polemical verve, Ettore Scola’s sly silences, Vittorio Gassman’s discreet arrivals, and card games until late at night.

Today, the tavern of the Menghi brothers no longer exists. In its place, we find Caffè dei Pittori, frequented by architecture students from the nearby faculty. The fiaschetteria Beltramme and Otello alla Concordia are still there, on Via della Croce. Although changed and mostly frequented by tourists, perhaps, with a bit of imagination, one can listen to the echo of those evenings.