Aromatic and intense – a few sips of grappa warm the soul and make for a refined end to any evening. It’s time to discover a bit more about Italy’s famed distillate.

Grappa has been on an international ascendancy. Once a drink most people outside of the Bel Paese first encountered post-meal at an Italian restaurant, grappa is fast becoming a highly sought after, nuanced liquor appreciated by connoisseurs the world over. So, as its popularity grows, it’s time to get to know more about grappa and how it can be best appreciated.

What is Grappa

Grappa is a popular distilled spirit produced from grape pomace. At times referred to as firewater for its high alcohol content – generally ranging around 40%-45% abv but with some exceptions coming in anywhere from 35%-65% abv – it is often served as a post-meal digestif or alongside a hot shot of espresso.

Not unique to any one region of the country, bottles of grappa can be found from the northern regions of Trentino Alto Adige, Friuli, and Piemonte, to the sunny island of Sicily – each expressing its individual grape variety and terroir.

How Grappa is Produced

Made from the leftover mix of crushed grapes, seeds, stalks, and stems, known as pomace or vinaccia in Italian, that remains post-wine making – grappa is the perfect example of leaving nothing to go to waste.

The fresh pomace is sent to a distillery where the first step is to ferment any of the non-fermented pomaces that comes from the production of white wines. Pomace that has already undergone this process, during the production of red wine, for example, is ready and doesn’t require this extra initial step.

The pomace is then placed in copper stills that are sealed and heated from the bottom. The steam that is created allows the pomace to begin to gently separate, releasing the alcohol and essence of the aromas from the grapes.

At this point, it’s the turn of the master distiller to control the vapors and aromas, ensuring that the heart remains while the tail, an oily substance, and the head, which contains methyl alcohol, are eliminated. The result is a strong liquid concentration with an abv of 65%-85% that is either clear or tinted depending on the type of grape variety that was used. To this, either mineralized or distilled water is then added to dilute the high levels of alcohol.

Depending on the style of grappa desired, at this point, it is either bottled or placed in barrels to age. Four types of grappa exist: Giovane or Bianca – unaged, young grappa; Affinato in Legno – refined in wood barrel for a short period of time; Vecchia or Invecchiata – aged at least 12 months in barrel: and, Riserva or Stravecchia – aged for at least 18 months in barrel. The barrels are usually oak, but some producers choose cherry, ash, or acacia instead depending on the aromas they want to impart. There are no limits as to how long grappa can be aged.

The History of Grappa

Though legend has it that grappa was first created in the town of Bassano del Grappa by Roman soldiers who had stollen distilling equipment from the Egyptians, it is more likely that the distillation of grape pomace first began in the Veneto region during the 13thor 14th centuries, with a large portion exported from Venice to countries in northern Europe.

Considered a medicinal cure for treating gout and even the plague, its production was reserved to pharmacists and doctors, as noted in Michele Savonarola’s work ‘De arte confetionis acquae vitae’ that was written in 1400. However, farming families all over the countryside began using their ingenuity to create makeshift stills to produce their own spirit from their leftover grape pomace, which they began to drink as much for pleasure as for medicinal purposes. Often referred to as graspa, trape, or grapa, it is believed that its name was derived from these dialectical terms adopted by these homemade distillers.

To control this illicit production an association to regulate the distillation of grappa was established in Venice in the 17th century. Yet, as regulations began to spring up, so did illegal home production – a custom that eventually earned grappa the nicknames filu or ferru. Meaning wire or iron in dialect, the terms derived from the way moonshiners would hide their liquor by wrapping an iron wire around the neck of each bottle before burying them around their property. While an innocent passerby would be unaware of the buried bottles, the distiller’s trained eye knew to look for the reddish stain left on the soil by the iron in the wire, creating a sort of rum runner’s map of buried spirits.

The Characteristics of Grappa

The characteristics of grappa vary depending on the grape variety used in the pomace – a factor that also determines whether a grappa is clear or slightly tinted. Generally fruity with floral notes, each variety will impart its unique aromas, for example, Cabernet Sauvignon gives a red berry flavor, while grappa made from the Moscato variety often has a hint of sweetness. Even pomace from dessert wines can be made into grappa, for example, platinum grappa made from the pomace of Recioto di Amarone offers a balance of honey and sour plums. Just like wines, those aged for longer tend to have more intense aromas often with hints of caramel.

Not categorized as a DOC with a protected designation of origin, grappa is an IG in the Italian labeling system meaning that it does have a protected geographical indication. To be considered truly grappa, the product must be made entirely within Italy.

Other indicators to note when looking for a grappa are on the label. Grappa vitigno is a grappa made from a single grape variety, while grappa aromatica is made strictly from aromatic grape varieties, and grappa aromatizza is flavored with fruit or herbs like chamomile, and even honey.

How to Serve Grappa

Grappa is generally served at room temperature, but how long it was aged for can also affect this choice. Younger grappa is best served at a cooler temperature of about 10°C (50°F) while aged versions prefer slightly warmer serving temps of about 16°C-18°C (60.8°F-64.4°F). It’s not common to drink grappa on the rocks since the fragrant oils extracted from the grape pomace could easily be masked by the cold.

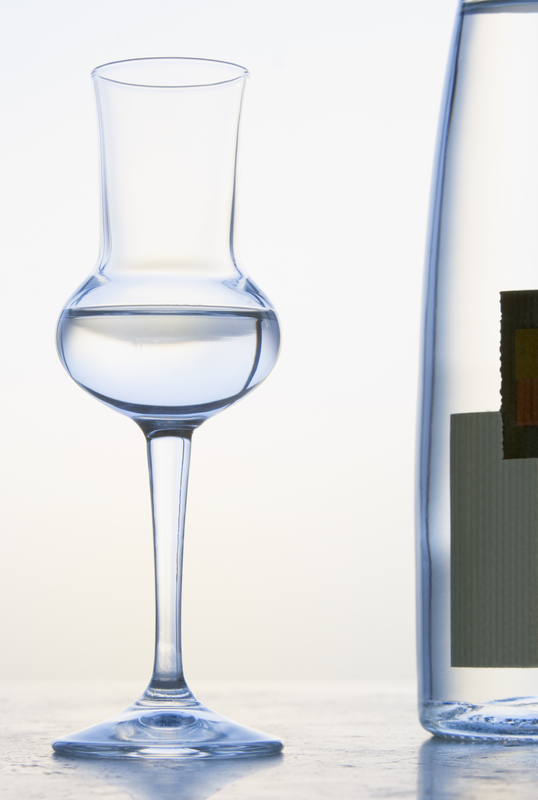

The correct glass is also key. Grappa should be served in a glass that is tall and narrow with a slightly wider opening to allow the aromas to be appreciated.

It’s custom to serve grappa at the end of a meal or sometimes to add it to espresso to create what is known as a caffè corretto. In Veneto, it can be used as a chaser, by pouring a drop into an espresso cup after finishing the coffee.

Grappa can also be paired with fruit. Serve a young grappa with fresh fruit like apples, pears, peaches, or pineapple. Consider serving an aged grappa with dried fruit instead to bring out the toasted nuances.

It also makes a wonderful pairing with chocolate. Aim for chocolates that are neither too bitter nor too sweet – a 60%-70% dark chocolate would be perfect with a grappa made with Nebbiolo, while an aromatic grappa, like one made with Moscato, would find its ideal match in a milk chocolate pairing.

Beyond its traditional customs, grappa which has seen a marked rise in international interest and collectors, has also caught the eye of mixologists now showing up on cocktail menus in new drink combinations like Grappa Tonic or Grappa Flip.

By Liana Bicchieri